And they’re concerned an extra 93,805 wells could become orphaned given Alberta’s economic outlook, completely overwhelming clean-up efforts

Geoffrey Morgan

Updated: December 18, 2019

Calgary Herald

Geriatric orphan wells, boomtowns going bust and the fate of coal-mining towns in the age of renewables: In a four-part series, FP visits Alberta’s forgotten small communities to see how they are struggling with changes in the broader economy.

CALGARY – In 1897, a German aristocrat named Count Alfred von Hammerstein was on a journey to the Yukon, where he hoped to make a fortune during the Klondike gold rush. As he arrived in what would later be called Alberta, he decided to stay and try to exploit the reserves of black gold in the oilsands.

Von Hammerstein raised money to sail drilling crews down the Athabasca River on sometimes ill-fated expeditions north of Fort McMurray. On one river trip, two members of the crew drowned. On another, the count’s leg was injured in what historical records vaguely describe as a “shooting accident.” In the end, the 14 wells he drilled, all before 1909, were unsuccessful.

The count learned “the oilsands would not give up their secrets easily,” according to an Alberta government report written in 1978, but he has since been ensconced as “one of the most colourful characters” in the Canadian Petroleum Hall of Fame.

But one of the wells von Hammerstein drilled has a more inglorious history. The well, drilled in 1906 or 1907 near the First Nations community of Fort McKay, is believed to be the province’s oldest orphan well, meaning nobody is financially responsible for cleaning it up.

Von Hammerstein died in 1941, long before wildcatters needed reclamation certificates for the wells they drilled. Indeed, the count never even obtained a drilling licence.

That well may be the oldest orphan, but it’s not an outlier since there are some 3,406 orphan wells listed in the Orphan Well Association’s clean-up list and that’s not sitting well with landowners.

Farmers, ranchers and their lawyers say they’re furious that oil and gas companies are failing to clean up after themselves and they’re concerned that an additional 93,805 inactive wells could become orphaned given Alberta’s economic outlook, which would completely overwhelm both the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) and the provincial government.

“The claim that Alberta’s oil and gas is the most ethically produced oil because of the environmentally and socially responsible way in which it’s produced is true only to an extent, and where it’s not true and where the government and industry need to up their game is in dealing with the legacy wells,” said Keith Wilson, a St. Albert, Alta.-based lawyer who represents landowners in fights with energy companies.

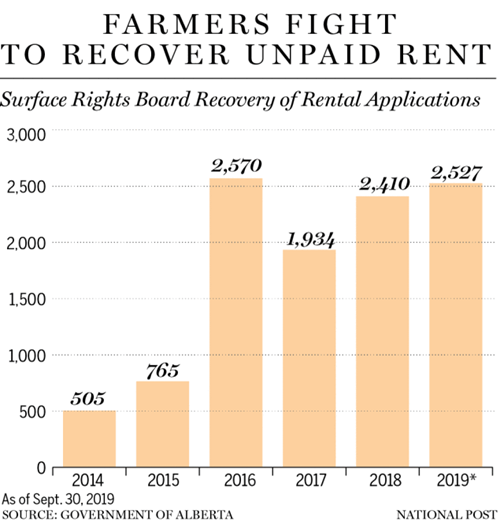

Wilson said farmers and ranchers have historically counted themselves among the energy industry’s biggest supporters and they routinely sign lease agreements that allow companies to access their land. But the relationship has soured as Alberta’s economy has tanked and landowners encounter problems with both collecting rental payments and getting companies to clean up old contaminated sites.

Geriatric orphan wells such as Von Hammerstein’s are a particular sore spot for farmers, because older wells are more likely to contaminate the ground, are more difficult to clean up and take more time to remediate since they were drilled in an age when environmental standards were more lax.

Wilson, who has fought in court to force delinquent companies into cleaning up geriatric wells, said older wells are also more likely to be plagued with rusted out down-hole equipment and he frequently sees wells with cracked cement linings, leading to an increased likelihood that contaminants will flow into the earth.

Moreover, he said, most oil and gas companies prior to the 1990s used pits, dug right next to a well, rather than tanks, to store the fluids and mud used in drilling the well and production. Those pits, he said, dramatically complicate the remediation efforts of older wells because freezing and thawing every winter and spring sends the contaminants deeper into the ground, further spreading any contamination.

Satellite images show one old orphan well near Lloydminster, on the Alberta/Saskatchewan border, encircled by an unnaturally dark shade of brown. The well was drilled during the Second World War on July 25, 1941, and produced a total of 17,052 barrels of oil. Now, 78 years later, it has yet to be fully remediated.

“If you’re an oil company and you’ve got 1,000 old inactive wells and you’ve got 100 new inactive wells, you can probably clean up all those new minimum-disturbance, coal-bed methane wells for the cost of cleaning up one or two of those old historic 1950s-era wells,” Wilson said.

In November 2018, the AER issued a statement that pinned the environmental liability for cleaning up oil and gas infrastructure in the province at $58.65 billion. That admission came after one of the regulator’s vice-presidents said during a presentation that the number could be as high as $260 billion, a figure that included oilsands mining remediation.

Either way, the problem is daunting.

The Financial Post sorted through well data from before 1964, the year the Alberta government started requiring companies to obtain reclamation certificates for cleaning up their oil and gas wells, and found 6,077 wells that are still active today. An additional 5,487 wells have suspended production but have not been cleaned up, and 3,695 wells have been plugged, a state the industry and government calls “abandoned,” but not remediated.

Altogether, there are 15,259 wells drilled before 1964 that have not been remediated, or 39.6 per cent of 38,491 wells drilled before that date.

In addition, 18,266 of the wells drilled prior to 1964 are exempt from reclamation certificates.

“Not every old one is complicated,” said Lars DePauw, executive director of the Orphan Well Association (OWA), which is funded through a levy paid by the industry and collected by the AER.

DePauw said the association prioritizes wells to clean up by their potential threat to public safety. Any well that could be releasing hydrogen disulphide gas is cleaned up first. He said the OWA targets wells in specific regions in area-based closure programs. “After that, we get to chronology,” he said.

Since November 2018, the OWA has been working on Von Hammerstein’s orphan well. It first plugged the well with cement, monitored it for a year and then capped the well bore last month, though additional work is being planned.

The OWA had been remediating 60 wells per year, but the oil price crash and resulting bankruptcies have forced the association to increase that to 1,000 annually.

One of the largest single funders of the OWA, by virtue of its size, is Calgary-based Canadian Natural Resources Ltd.

According to farmers and surface rights lawyers, CNRL, which produces more than one million barrels of oil and gas per day, is also one of the most active at cleaning up.

The company is a “top performer” in the number of inactive wells it reclaims, spokesperson Nicholas Gafuik said in an emailed statement. “In 2018, we abandoned 1,293 wells and submitted 1,012 reclamation certificates. In 2019, Canadian Natural is targeting approximately 2,000 wells to be abandoned.”

Gafuik said the company supports the AER’s area-based closure approach because it accelerates the pace of reclamation by being cost effective. “By strategically grouping well and pipeline abandonment by area, we increase efficiencies and manage our impact on the land better,” he said.

Farmers and lawyers praise CNRL’s pro-activeness and the OWA’s attempt to accelerate remediation efforts, but remain concerned by the magnitude of the problem. At the current pace, it would take the OWA and CNRL, the two most active well remediation organizations in the province, 32 years to clean up all the inactive and orphan wells in Alberta.

Daryl Bennett, a farmer in the Municipal District of Taber, said he has wells drilled in the 1940s and 1950s on his property. He calls them “bottom dwellers” and his frustration getting them remediated led him to get involved with local surface rights groups and advocate on behalf of farmers and ranchers dealing with oil and gas producers.

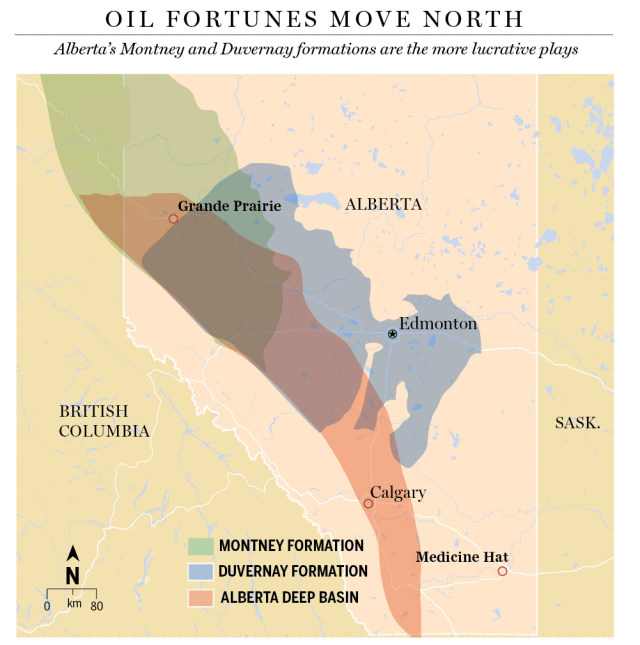

Given the challenges inherent in cleaning up older wells, Bennett said he and other landowners in Southern Alberta have been seeking approvals to build solar power installations on top of old well sites. Renewable power installations, he said, would allow farmers to earn money off land that has previously been contaminated.

“At some point, (the Alberta government or the OWA) are going to be buying some land,” he said.

Other landowners are concerned that given the dire state of Alberta’s economy — anemic economic growth, provincial government austerity budgets and low commodity prices — the unfunded liability will be dropped on farmers and ranchers.

“Knock on wood, hope the landowner won’t be doing the reclamation,” said Graham Gilchrist, principal at Gilchrist Consulting in Leduc, who advises farmers and ranchers in the area around Edmonton on dealing with orphan wells and delinquent rental payments from energy companies.

Gilchrist and Bennett both believe Alberta needs a bonding system that forces companies wanting to drill a well to first post collateral so that neither taxpayers nor landowners are ever responsible for the costs of cleaning up orphaned or inactive oil wells.

Lawyers and researchers have also described the need for legislated time limits on cleaning up inactive wells, which they said would dramatically reduce the backlog of 93,805 inactive wells that could be tomorrow’s orphans.

In both Texas and North Dakota, two states that produce large volumes of oil and gas, bonds and time limits have resulted in far fewer orphaned wells and fewer long-term inactive wells than exist in Alberta. Texas was also able to reduce its backlog of orphan sites.

In years past, the Alberta government and industry groups have resisted set time limits to clean up old wells because they said inactive older wells can still be economically viable during periods of higher oil and gas prices.

But historical data show that 60-year-old wells only have a one-per-cent chance of being reactivated in that scenario, according to a study by University of Calgary economist Lucija Muehlenbachs that was published in the International Economic Review in February 2015.

“The probability that an inactive well is going to be reactivated decreases the older it is,” she said. “These inactive wells are not getting reactivated.”

Time limits in Alberta have been successful in the past, but the province has not required bonds prior to drilling activity.

Alberta regulators first introduced a “special well fund” to finance the cost of plugging wells in 1986. Then, in 1993, the government introduced the first levy for orphan wells and began screening the risk that oil and gas companies might orphan their wells by keeping a ratio of how many inactive wells a company owns relative to its active wells.

The government in 1997 then implemented the Long Term Inactive Well Program, which pushed oil and gas companies to be more proactive within stricter time limits.

“That 1997 program was pretty effective,” said Barry Robinson, a lawyer at Ecojustice Canada who acts on behalf of farmers and ranchers, noting that the program included a five-year time frame for plugging inactive oil and gas wells.

That program was replaced in 2000 with the current system that does not include time limits on well remediation.

Robinson said one client in Pincher Creek, in the southwestern corner of the province, has a well that was drilled on his land in 1957.

“This well was drilled when his father owned the land and now he’s saying, ‘I don’t want to pass this onto my kid,’” he said, noting the problem has become an intergenerational one.

This well was drilled when his father owned the land and now he’s saying, ‘I don’t want to pass this onto my kid’

Barry Robinson, a lawyer at Ecojustice Canada

In 1995, Robinson said, there were 12,000 inactive wells in Alberta, but that has since ballooned 680 per cent.

A February 2018 presentation by Robert Wadsworth, AER vice-president, closure and liability, showed the number of inactive wells has grown at a rate of six per cent per year since 2000.

Alberta’s current government faces a dual challenge when dealing with the problem. Farmers and ranchers voted in massive numbers for the United Conservatives in the provincial election earlier this year, helping UCP candidates beat NDP candidates in many rural ridings by tens of thousands of votes. However, the UCP also promised to reinvigorate the energy sector by removing red tape and encouraging investment.

Now, with two parts of the government’s support base locked in fights over orphan wells, delinquent rental payments and rural property tax arrears, the province is reconsidering existing legislation as it conducts a full review of the AER.

“Currently, the government is working with the Alberta Energy Regulator and industry to review the liability management framework in Alberta,” Energy Minister Sonya Savage said in an email. “Our government wants to ensure that the economic environment exists for private industry to be successful and able to bear the costs of well abandonment.”

In recent weeks, Premier Jason Kenney has asked Ottawa for financial assistance to help remediate orphaned wells as a way to put unemployed oil and gas workers in rural areas back to work.

Various provincial governments in Alberta, including the recently ousted NDP, have formed panels on how to handle the problem of orphan wells, but it has only continued to grow in the 114 years since Alberta was formed.

Indeed, Alfred von Hammerstein’s orphan well north of Fort McMurray has remained unremediated for almost the entire history of the province, which was created by former prime minister Wilfrid Laurier in 1905. Thousands of other old inactive wells and legacy orphan wells have never been cleaned up either.

“What we’re seeing is a complete lack of action,” said Wilson, adding that company money during oil booms typically gets allocated to new drilling programs, while government money is allocated to building new infrastructure. “The excuse that these wells can be economic and reactivated if prices return to historic highs is false, because we’ve been through those cycles and no work has been done.”

Financial Post