Geoffrey Morgan

December 12, 2019

11:29 AM EST

Last Updated

December 13, 2019

11:48 AM EST

Financial Post

Oil companies’ late or delinquent payments on land leases and municipal taxes are exposing fissures in Alberta’s rural communities

Geriatric orphan wells, boomtowns going bust and the fate of coal-mining towns in the age of renewables. In a four-part series, FP visits Alberta’s forgotten small communities to see how they are struggling with changes in the broader economy.

CALGARY – Andy Hofer and members of his Hutterite colony in northwestern Alberta have been embroiled in an increasingly common dispute in recent years. So common that the Hutterian Brethren Church of Grandview, where Hofer is the field manager, has been in at least eight such disputes in the past year.

Like many farms in the province, the religious agricultural commune, in an attempt to supplement its income, has signed lease agreements with oil and gas companies that want to drill their land for hydrocarbons.

But as commodity prices have tumbled for both oil and natural gas, those rental payments have either dried up or, in some cases, disappeared. In the past year alone, the Hutterite colony has won eight cases at the Alberta Surface Rights Board against energy companies that either weren’t paying rent or tried to unilaterally reduce their rental payments.

See Also:

- Far from the spotlight, small-town Alberta suffers in upheaval sweeping energy sector

- A tale of two Alberta towns: One in the throes of a boom, the other mired in the energy downturn

- Retraining oil and gas workers sounds like an easy solution, but the reality is incredibly complex

“It was a fight at the start,” said Hofer, adding that his colony near Grande Prairie has 80 such lease agreements. “They tried to reduce (the rent) and it was difficult getting more money.”

What was once a mutually profitable relationship between oil companies and the farmers, ranchers and counties who own the land they work on has become increasingly strained in recent years. Landowners and county reeves say they’ve had to fight for both rent and even municipal tax payments from a growing number of energy producers.

Those fights have resulted in drawn-out legal battles with companies farmers and ranchers once considered partners, while counties with massive municipal property tax arrears are being forced to dip into savings to balance their budgets or pass additional costs onto residents, who are sometimes the same farmers dealing with unpaid oil and gas rents.

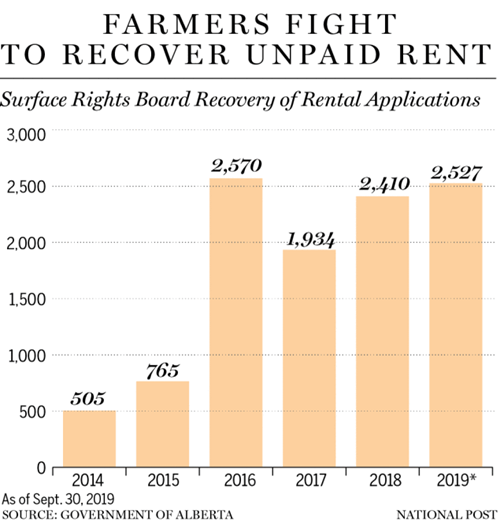

The problem has become so widespread that applications to the Surface Rights Board, the provincial tribunal that assists landowners, occupants and operators resolve disputes about surface access and compensation, to recover unpaid rents have soared.

More than 2,500 applications were made in the first nine months of 2019 compared to 505 motions in all of 2014. The number of applications so far in 2019 has already surpassed the entire 2018 total of 2,410.

“The board is swamped,” said Daryl Bennett, a farmer and advocate for landowners in the Municipal District of Taber, just east of Lethbridge.

He said landowners are forced to wait years for payment decisions as a result of the glut of applications and some long-awaited decisions are rendered with “lots of mistakes” since the board does not have the staff required to properly deal with the volume of complaints.

One thing is clear: the delinquent payments are exposing fissures in Alberta’s rural communities.

Farmers and ranchers own the surface rights to the land, while oil and gas companies own the mineral rights beneath the surface. Contracts in years past were negotiated to allow both sides to profit as farmers and ranchers could earn rental income by allowing exploration and production companies to put drilling rigs and pump jacks on their lands and exploit any reserves.

When the lease payments stop — either due to bankruptcy or companies looking to reduce their rent — landowners don’t have the luxury of handing out an eviction notice. Once a well is drilled and encased in cement, it’s a permanent fixture on the land until its fully remediated and that process takes years.

Increasingly, landowners are angry about having to chase oil companies for payments and, sometimes being forced to wait years for the Surface Rights Board to settle the disputes. At the same time, Canadian agricultural exports have been shut out of critical markets such as China, further handicapping already cash-strapped farms and ranches.

The agriculture sector is also competing for space on railway lines to move their grain to ports, because oil companies are shipping more of their product on rail cars due to the shortage of pipelines.

Oil-by-rail exports hit 319,594 barrels per day in September, which is approaching the record high of 337,260 bpd set in December 2018 and double the five-year average of 159,584 bpd, according to the Canada Energy Regulator.

Canadian National Railway Co. data show it has moved 8.8 million tonnes of Western Canadian bulk grain this year through the end of November, which is a six per cent decrease relative to last year and a two per cent decrease relative to the three-year average.

But more than just farmers and ranchers are affected by energy companies looking to reduce their expenses.

County reeves and representatives for rural districts report that companies, particularly natural gas producers that have struggled with low commodity prices in recent years, are either late or delinquent in paying their municipal taxes.

Rural Municipalities of Alberta (RMA) president Al Kemmere said counties and rural municipalities “are seeing an increase in the number of taxes not being able to be collected compared with last year.”

Last year, the association reported communities were unable to collect $81 million in municipal taxes, with most of the arrears coming from energy sector companies.

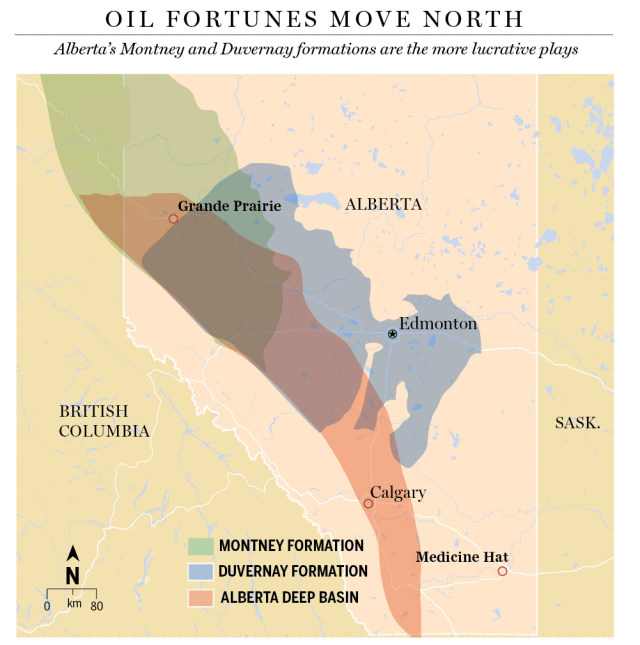

The strain is exposing financial weaknesses in different pockets of Alberta, because oil and gas exploration and production has moved from conventional formations in the south to more lucrative, deeper-lying unconventional formations such as the Montney, Duvernay and oilsands in the north.

A review of the balance sheets of every rural municipality and county in the province finds a large division in the financial fortunes of Alberta’s counties in the deep south and those sitting on hot plays in the north.

The financial statements show that counties and rural municipalities in active oil and gas hotspots have accumulated large surpluses. For example, Wood Buffalo is home to the oilsands and reported a $5-billion surplus in 2018. The County of Grande Prairie, at the heart of the Montney and Duvernay formations, has a surplus of $543 million.

The 10 richest counties and rural municipal districts in the province have accumulated surpluses totalling $9.5 billion, about half as large as Alberta’s $18.1-billion Heritage Fund, which was established by former premier Peter Lougheed as the province’s long-term savings plan.

By contrast, the richest county in the province’s southeast, Cypress County, has an accumulated surplus of $244 million, only good enough for the 18th-highest reserves in the province.

“The conventional play is dying out. It’s never going to come back the way it was,” Bennett said, adding that landowners in the south are looking at ways to repurpose the unremediated land left behind by bankrupt oil and gas companies because they no longer believe the wells in those areas will be bought by new operators.

Cypress County is home to older natural gas infrastructure around Medicine Hat, but areas in the south, which are no longer beehives of oil and gas activity, have average cash reserves of $143 million.

Some counties in the area have watched multiple bankrupt oil and gas companies such as Trident Exploration Corp. and Houston Oil & Gas Ltd. hand responsibility for cleaning up their aging wells to the Orphan Well Association, an independent non‐profit organization under the Alberta Energy Regulator.

“What it does create now more than anything is a situation where some have and some don’t have. We’re going to have to work with the provincial government on the distribution of the (municipalities grant) that we have from the province,” Kemmere said.