A pump jack on land south of Calgary, whose owner fears the well will soon be considered orphaned. Chris Bolin/Chris Bolin

A pump jack on land south of Calgary, whose owner fears the well will soon be considered orphaned. Chris Bolin/Chris BolinAs companies in Alberta’s oil patch fight for survival, some are not decommissioning and cleaning up old sites, reports Kelly Cryderman

But the dramatic crude price drop that began in mid-2014 means many energy companies, especially smaller producers, are fighting for their survival. If a wave of weaker oil and natural gas companies go bust before doing legally required end-of-life work, they will leave multiple “orphan” wells behind.

“In my mind, there’s no winner here. It’s going to cost somebody, and possibly the taxpayer in the end,” says Patricia Walker, a High River, Alta.-based consultant hired by landowners to help with disputes with energy firms.

To help protect the province from the financial risk of a massive environmental cleanup of old wells, the government has required companies to have enough assets or keep enough funds on hand to properly decommission their own sites. And even if this system doesn’t work, the oil industry as a whole funds an Orphan Well Association that works to seal up and “reclaim” the land around old, unwanted wells.

But there are warning signs the oil-price rout – and another year of casualties for Canadian junior and intermediate oil and gas companies – could dampen enthusiasm for the continuing care of the province’s well sites. According to Sayer Energy Advisors, 20 oil and gas companies went into receivership in 2015, compared with a typical annual average of around eight. Companies with larger inventories of wells could be “the next big blow up,” according to a report from the firm earlier this year.

Gale Tharle, a 4th-generation Alberta rancher, is photographed on his land an hour south of Calgary.

Gale Tharle, a 4th-generation Alberta rancher, is photographed on his land an hour south of Calgary.

Chris Bolin

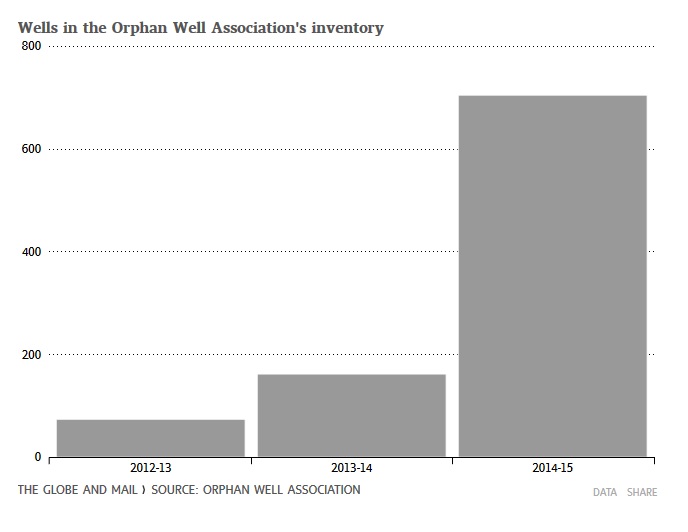

Already, the last 18 months have seen a major increase in the workload for Alberta’s Orphan Well Association. The number of orphan wells awaiting cleanup jumped significantly, going to around 700 from a previous total of 162. And a government-funded board forecasts that this year will see a dramatic increase in the government’s tab for lease payments to farmers and other landowners – meaning many small oil and gas companies no longer have the available cash to service their most basic of business costs.

Ms. Walker said her company, My Landman Group Inc., is helping Gale Tharle, a landowner near Mossleigh, Alta., who hasn’t been paid rent by the small oil producer who has one well on his land for three years. The rancher is now involved in a complex quest to receive the rent he is due, and is also grappling with invasive weeds, an old working shack with broken windows, and a pump-jack in disrepair on his land. Ms. Walker believes the insolvent company’s assets will eventually end up being added to the Orphan Well Association’s rolls.

“It looks like everybody will be out of luck.”

According to the Alberta Energy Regulator, more than 440,000 wells have been drilled in the province since 1963. Of those, 67,000 have been sealed up in a process called abandonment by the oil and gas industry and 105,000 have been both abandoned and have had the land cleaned up (reclaimed).

Of those that remain, many are still in use and have a productive life ahead of them. But there are tens of thousands, at least, that need to be abandoned and reclaimed.

“Albertans expect that the polluter clean up their mess. There is room to improve the current policies. That is why this government is looking at ways to make improvements,” said Alberta Energy Minister Marg McCuaig-Boyd.

The NDP government is in talks with the Alberta Energy Regulator about how to best address the issue of aging energy-sector infrastructure, but the province doesn’t have rules governing specific timelines for when wells need to be cleaned up. Industry watchers say the cleanup of old well sites won’t be a priority for companies being forced to lay off workers and struggling to stay afloat.

“How many non-producing wells are just being left sitting out there with nothing being done to clean up the oil industry’s legacy?” said Edmonton-based landowner advocate and lawyer Keith Wilson, who has long expressed concerns about the costs of cleaning up a growing inventory of wells in the province.

Mr. Wilson and others say with no specific timeline attached to the cleanup, some oil companies will simply keep wells in an inactive or suspended state – and will therefore avoid the biggest cleanup costs that can sometimes run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, per well, or more. He worries some level of government, and citizens, will eventually end up footing the bill for the cleanup, including those sites with land and water contamination issues.

“The speed of the drop has really been challenging for the entire sector, globally,” said Brad Herald, a director of the Orphan Well Association and a vice-president at the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP).

But Mr. Herald also emphasized that many currently inactive wells are still assets, not liabilities, and may be returned to productive use when the time is right. He also said that wells from bankrupted companies are often sold to more solvent players, and it’s not a given that wells from insolvent companies will end up as orphans.

“Whenever there are companies in receivership, there’s more risk that we ultimately might see more orphans – and there are some sizable companies in receivership. But there’s also a fair bit of interest in the packages right now,” he said.

“It is great opportunity for companies if there is some cash flow elasticity to build their portfolio.”

And in Alberta, safeguards are in place to make sure that the “polluter pays” principle is upheld. One safeguard is the Alberta Energy Regulator’s licensee liability rating (LLR) program, which uses a comparison of assets to cleanup liability costs. When the liabilities outweigh the assets, the company must put up a cash deposit for the difference.

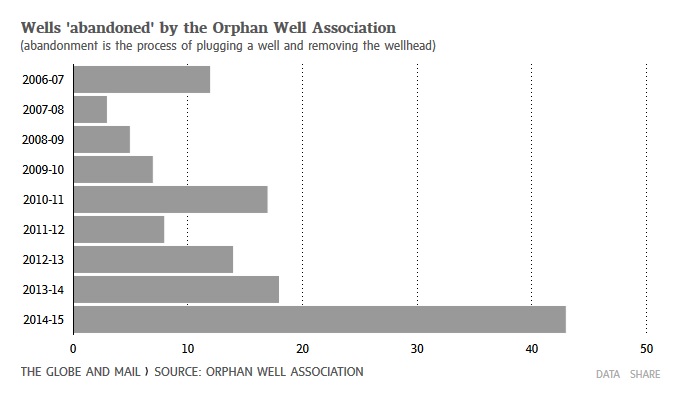

Even when the government’s system doesn’t work, and individual companies go bankrupt without cleaning up their old sites – there is a fail-safe. The Orphan Well Association, funded by industry levies, is designed to provide a safety net when companies fail and there is no market for their assets. Over the past 25 years, the industry has put more than $200-million into properly sealing and cleaning up old sites.

In light of the

economic conditions and the increased workload for the association, Mr. Herald notes the industry has doubled the association’s annual budget to $30-million from the previous $15-million.

There are also requests from some quarters to the federal government for cash. Last month, Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall called on Ottawa to come up with $156-million to clean up 1,000 non-producing wells in his province as a job stimulus program. And this week the Petrole

um Services Association of Canada made a similar request for Alberta’s much more numerous wells – asking for $500-million in federal infrastructure dollars to put a dent in the association’s estim

ate of about 75,000 inactive wells requiring abandonment and surface reclamation, with the similar argument the plan will create jobs, retain expertise, and provide economic and environmental benefits.

There is a precedent for a government infusion of cash for a cleanup: In the global downturn of 2008, the Alberta government gave an extra $30-million to the Orphan Well Association for cleanup work.

Both Mr. Wall and the association say the extraordinary economic fragility in Western Canada’s economy demands this type of response – and are looking to next week’s federal budget for news. Even critics such as Mr. Wilson concede it might be cheaper to clean up many of these sites sooner rather than later.

However, the downturn in the energy industry has also created a new source of discontent among the farmers of Alberta, who for decades have been sharing their land with oil and gas companies. If there are no environmental problems, many landowners are happy to receive the “rents” energy firms pay for access to the land and to compensate farmers for their loss of use of it.

But a growing cohort of mostly smaller firms, many financially strapped, have stopped making these rent payments on their wells, especially in the last two years. In cases where energy companies don’t pay, the Alberta government is supposed to pay the landowner and chase after the company to be reimbursed.

The Surface Rights Board – a quasi-judicial body that helps resolve disputes between landowners and mineral rights holders – has been overwhelmed by an increase in work and costs related to unpaid rents.

The board paid out more than $1.7-million in 2015, compared with about $722,000 in 2014. Chairman Gerald Hawranik forecasts government-funded payouts to landowners for rents they are owed by energy companies will hit $3.5-million in the coming fiscal year.

“It has been escalating,” Mr. Hawranik said. “Almost every month there are more applications.”